This image is widely portrayed as a British and German soldier exchanging cigarettes on Christmas Day of 1914 during the Truce. The reality? The caption on the IWM site states, Battle of Epehy. British wounded and German prisoner sharing a cigarette at an advanced dressing station near Epehy, 18 September 1918. Note captured German Maxim 08/15 (Spandau) light machine guns in the background. IWM Ref No Q 11538

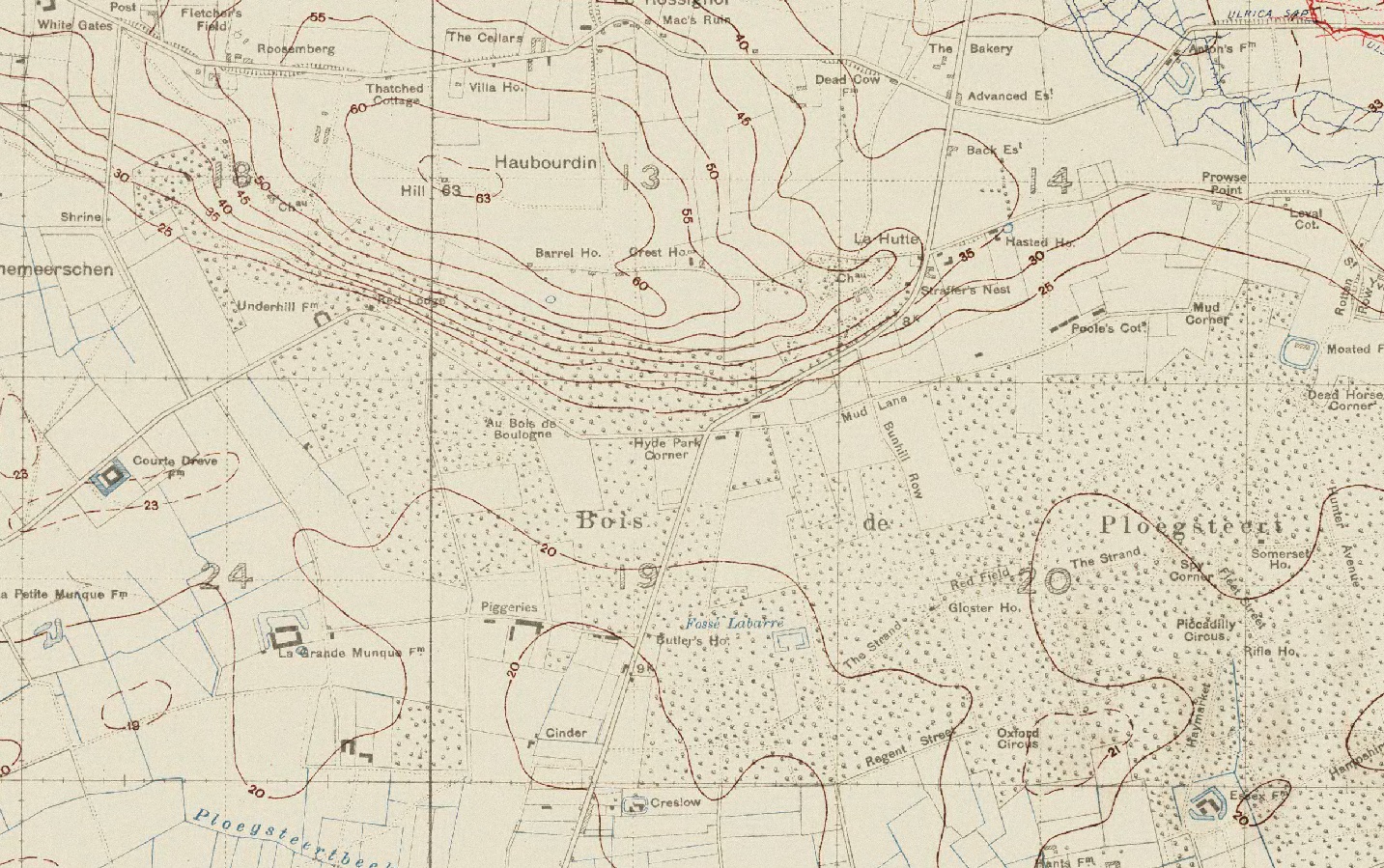

On 14 December an attack was launched by the 8th Brigade at Wytschaete; this failed with heavy casualties. On 18 December 1914, another attack was launched by the 22nd Brigade at La Boutillerie; this also failed with heavy casualties. It’s important to note this because this will have a bearing on what I cover later on in this blog.

The famous wartime cartoonist Bruce Bairnsfather recounted an episode that has been leapt on by others and it became one of the focal points for many of the centenary events in held in 2014. This included the abomination that is now the football memorial that stands close to St Yvon and on the edge of Ploegsteert Wood, known as Plugstreet Wood to the British soldiers who served there.

He stated:

Around noon, a football match was suggested. Someone had evidently received a deflated football as a Christmas present.

This mention of football came forty years after the event when he was interviewed in 1954 for a television piece. And, according to Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch, two English soldiers brought a football to the German trenches. The first account is false and the writings of Lt Zehmisch have been misinterpreted. I will come onto those later.

Also, in an online article in The Telegraph, dated 11 December 2014, the title stated:

‘Belgian monument unveiled to mark “humanity” of British and German soldiers who put down their arms and left their trenches to play football during an unofficial truce on Christmas Day 1914’.

These headlines and articles were printed all over the world and there is that romanitised notion that men got out of their trenches and all played a jolly old game of football in no-man’s-land when the guns fell silent. Except that football between the British and Germans never took place at St Yvon and so the memorial to it is citing a piece of history that did not happen there.

With regards to images of the Christmas Truce you have to be very careful. There are accurate images of the event, but none that portray men playing football and many of them are duff history because they come from another time. A big clue to all of them is if you see both sides wearing helmets then they are not Christmas Truce because helmets were not widely issued to both sides until 1916.

The Christmas Truce that occurred on 25 December 1914 is fact and there are numerous accounts from the time that confirm this. But what is not as easy to confirm is the notion that both sides played football against each other. Certainly, many of the veterans who were there that day refute this and there are few primary sources that mention this occurring.

Another duff history image which people think comes from the Christmas Truce of 1914. The reality is this image comes from a football match which was played at St Yvon in 2014.

Secondly, this has not been helped because we also have accounts from veterans recorded later on, such as that made by Ernie Williams in 1983, who had served with the 1/6th Cheshire Regiment, where he states:

The ball appeared from somewhere, I don’t know where, but it came from their side—it wasn’t from our side that the ball came. They made up some goals and one fellow went in goal and then it was just a general kick about. I should think there were about a couple of hundred taking part. I had a go at the ball. I was pretty good then, at 19. Everybody seemed to be enjoying themselves. There was no sort of illwill between us. There was no referee, and no score, no tally at all. It was simply a melee—nothing like the soccer you see on television. The boots we wore were a menace—those great big boots we had on—and in those days the balls were made of leather and they soon got very soggy.

This is now widely considered by experts to be a fabrication of the truth where Ernie Williams was almost prompted into saying what he felt the interviewer, Malcolm Brown, wanted to hear. It is reputed that Malcolm Brown himself did not believe Ernie’s tale. And certainly, when he is trying to intimate that football was played by hundreds of soldiers on both sides, surely if that were so, there would have been accounts from the time? So sadly, there is the misconception that all over the line this occurred.

The accounts and reports about football have to be carefully studied because virtually all of them are false mainly because they came out a good while after the event (e.g. in 1916 or even later on as with the case of Ernie Williams). Another example of how things get misinterpreted is this account, again in the same sector as where Bairnsfather served. Henry Williamson wrote about the Christmas Truce several times. He mentions football once in a fictional novel, A Fox Under My Cloak, published in 1955:

… a football was kicked into the air, and several men ran after it. The upshot was a match proposed between the two armies, to be held in a field between the German lines.

The watchword here is ‘proposed’. And yet the account by Henry Williams is also taken to be an accurate account of football being played by both sides.

The duff history UEFA memorial to football at Prowse Point near Ploegsteert Wood. Everything on this site is fake and the memorial, now given the nickname the ‘Rusty Bollard’ commemorates an event that did not happen here.

The other way that accounts come is from men serving in regiments that if you actually looked at where they were, they were not in the same place or can be discounted because of what others said at the time.

This is what Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton had to say about it in their excellent book Christmas Truce, which was first published in 1984 when we still had veterans who had witnessed the truce to speak to. I would urge anyone who is interested in reading more about the truth behind the Christmas Truce to read this book:

To many people it has come to be accepted that the central feature of the Christmas Truce was a game, or possibly games, of football in which British and Germans took part. Indeed, to some, the whole event is not so much ‘the truce’ as ‘the football match’. It is, of course, an attractive idea, carrying as it does not only the heart-warming thought of enemies at friendly play, but also the appealing if politically niave implication that nations would be far better employed in settling their differences in the fields of sport rather than on the field of war. Yet there are those, including some veterans of 1914, who doubt if any football match took place at all.

And this is why we have to state that Bairnsfather’s mentioning of football in the TV interview is not true.

Another favourite surrounding the duff history images for the Christmas Truce of 1914. The reality? The caption on the IWM site states, Battle of Pilckem Ridge. German prisoners waiting to be interrogated. Pilckem, 31 July 1917. Note a Gibraltar cuff-title worn by a German POW. The British soldiers on the right are probably servicemen of the Irish Guards. IWM Ref No Q 5724

Captain Robert Hamilton noted that ‘A’ Company of the 1st Battalion Warwickshires would have played the Saxons but were relieved. CSM George Beck wrote in his diary that the Germans shouted across a challenge to play football on Christmas Eve, but then there is no mention of a game being played. What we can also confirm is that ‘C’ Company of 1/RWK played a game among themselves. This is now generally agreed that this is the game mentioned by Lt Zehmisch of IR134, whose account from his diary actually says: ‘

The English brought a soccer ball from the trenches, and pretty soon a lively game ensued.

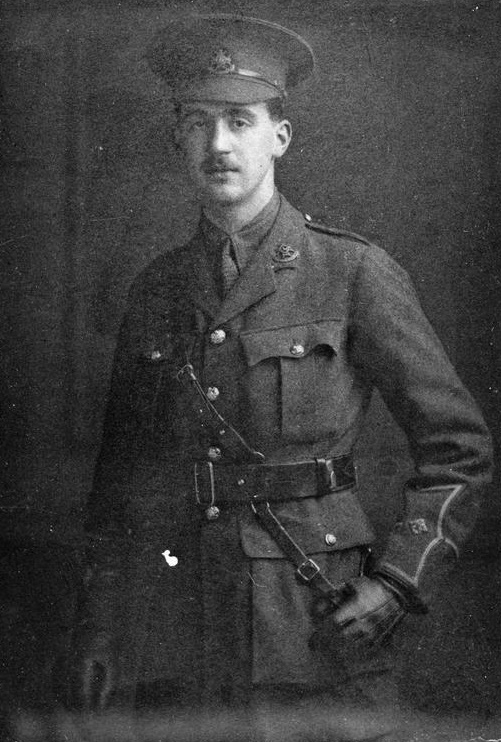

The famous image of Bairnsfather meeting a German soldier in no-man’s land on Christmas Day of 1914.

Bairnsfather details everything about the day in Bullets and Billets, and the main theme he concentrates on when he sees the Germans in no-man’s-land is this meeting:

I spotted a German officer, some sort of lieutenant I should think, and being a bit of a collector, I intimated to him that I had taken a fancy to some of his buttons. We both then said things to each other which neither understood, and agreed to do a swap. I brought out my wire clippers and, with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons and put them in my pocket. I then gave him two of mine in exchange.

So, if you visit the UEFA Memorial at Prowse Point, know that you are visiting a duff history site. Despite being told that no football was played there between both sides UEFA went ahead and had the memorial put in. So, sadly, it commemorates an event that didn’t take place, the trenches are nowhere near the front line and the bunker you see was moved there. It’s all fake.

The reality is that, of the thousands of men who may have taken part in the truce, only around twenty to thirty men may have played football with the Germans. We do have accounts from German soldiers, written soon after the truce, to state that they played against their British opponents, but it is one specific incident that only occurred in one specific part of the Western Front.

Two German soldiers, one called Johannes Niemann, both served in IR133 and Niemann recounts his experiences while serving in trenches on a frozen meadow at Frelinghien:

Then a Scot produced a football … a regular game of football began, with caps laid on the ground as goalposts. The frozen meadow was ideal [to play on]. One of us had a camera with us. Quickly the two sides gathered together in a group, all neatly lined up with the football in the middle.… The game ended 3:2 to Fritz.

The second account comes from a letter discovered more recently where the second soldier from IR133 wrote to his mother and mentioned, ‘playing ball with the English’ so this helps to confirm the account by Johannes Niemann and the position mentioned by Niemann correlates to his regiment playing against the 2nd Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. However, we do not have anything concrete from the 2nd A&SH to confirm they played against the Germans.

Now that is perhaps enough to confirm football being played on Christmas Day, but there is one more story that can be corroborated from the thousands of them out there, which we will now look at, and it involves the 1st Battalion, Norfolk Regiment. On Christmas Eve, the weather changed to a hard frost. In the evening, the Germans were seen to place Christmas trees with candles on their parapets and they are heard to be singing carols. It was here that something amazing would happen on Christmas Day.

Herbert Reeve was in the line for the truce but does not make mention of what others would witness during this time:

And so, came Christmas 1914. We received Princess Mary’s Christmas gift of pipe, tobacco and cigarettes, and I still have this in my possession, as issued. Then the fraternisation took place on Christmas Eve. My Company were in reserve line at the time.

It is little wonder when you look at that narrative that the reports of the Germans meeting the Norfolks was reported in a very official way by officers who reported back to GHQ. Of these reports, there are three in the war diary. The first comes from Lieutenant George Philip Burlton:

On December 25th I was in command of the right-hand fire trench of the Norfolk Regiment’s position. During the morning I noticed groups of the enemy and British Troops belonging to units if the 4th Division meeting half way between their trenches. At about 1 p.m., one of the enemy left the trench opposite our own and came unarmed toward us. I sent a Corporal to meet him half way. After a time more Germans crossed towards us and I allowed an equal number of my men to meet them. Seeing a German officer also out in the open I went to meet him myself. At about 2.30 p.m. all our men under my command were back in the trench.

But these reports aside, which make no mention of football, over a Twitter discussion about the 1st Battalion Norfolk Regiment and their involvement in the truce, it became very apparent that this battalion did play football in no-man’s land between the lines just to the north of the Wulverghem–Messines road.

In a newspaper cutting detailing the experiences of a soldier called Albert Wyatt, who came from Thetford, and who was in the trenches with the 1st Norfolks on 25 December.

Albert Wyatt’s account of his experiences in no man’s land printed in the Thetford Times soon after the event had occurred.

Football in the Firing Lines

Thetford Corporal Among the Players

The strange Christmas scenes which occurred in the British and German firing lines are described in a letter written by Corporal A. Wyatt to his parents a short while ago. He regards it as the most historic day ever spent on the battlefield. He says that when ‘A’ Company, 1st Norfolks to which he belongs arrived in the trenches on the 24th December they found everything quiet. There was no rifle firing. They had been in the trenches a short time when they heard someone singing Christmas hymns. Then all at once there were shouts of ‘Three cheers for the English’. To their surprise the voice came from the German trenches. ‘Then our men and the Germans,’ Corporal Wyatt proceeds, ‘started singing hymns together. The same thing carried on nearly all night and there was a sharp frost to make things look better. On Christmas morning it was very thick and we could not see far in front of us till about midday. Then we heard the Germans shouting, “Come over here, we will not fire!” They got out of their trenches and started walking about on the top. Our chaps, seeing them did the same. Then all at once came the surprise. The Germans started walking towards our trenches, and two or three of our chaps went out to meet them. When they met, the Germans speaking in English wished them a Merry Christmas. ‘Then came the fun. Everybody on each side walked out to the middle of the two firing lines and shaking hands wish each other Merry Christmas. To our surprise we found we were fighting men old enough to be our fathers, and they told us they had had enough of the war, as they were nearly all married men. ‘We finished up in the same old way, kicking footballs about between the firing lines. So, football in the firing line between the British and Germans is the truth as I was one that played.

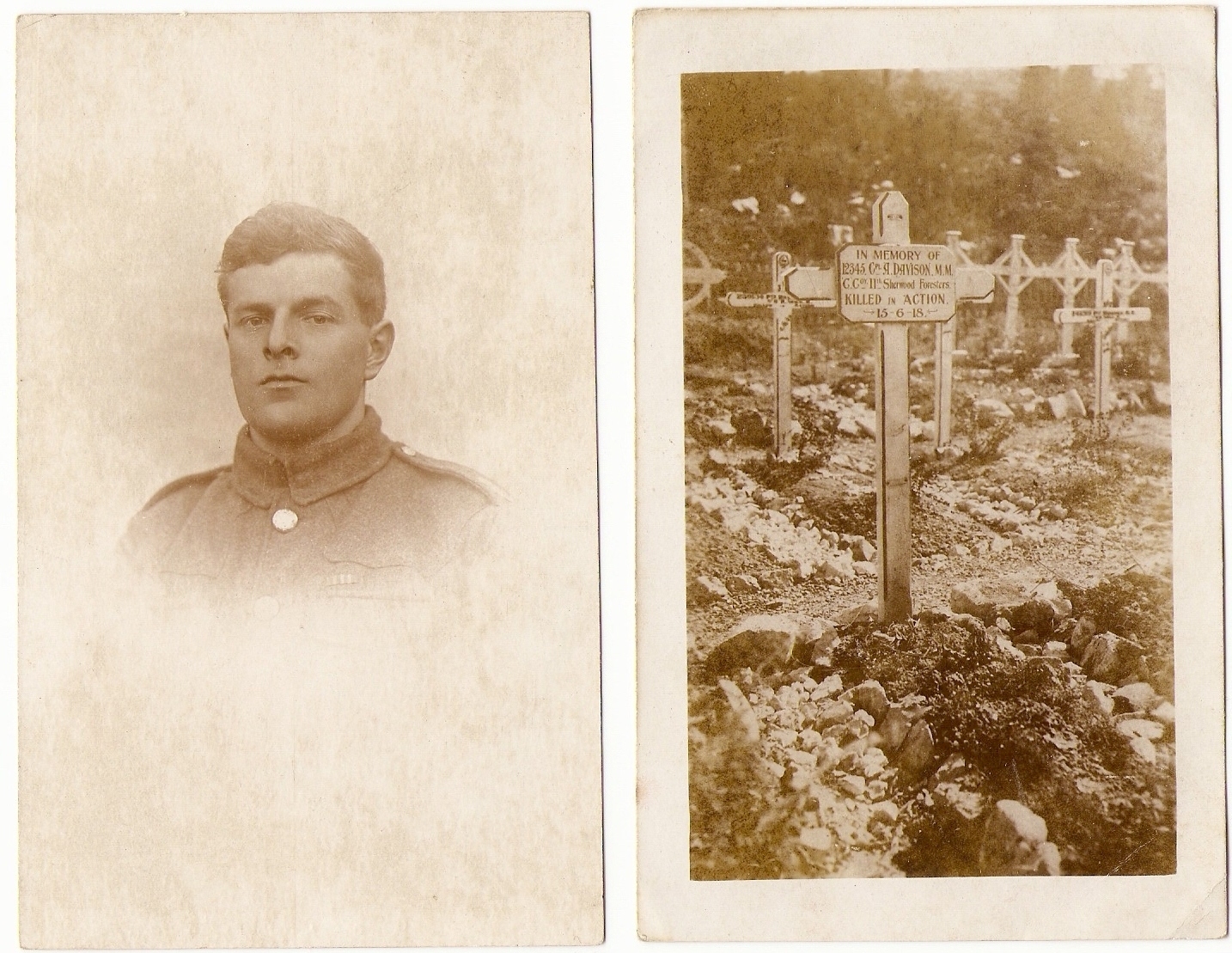

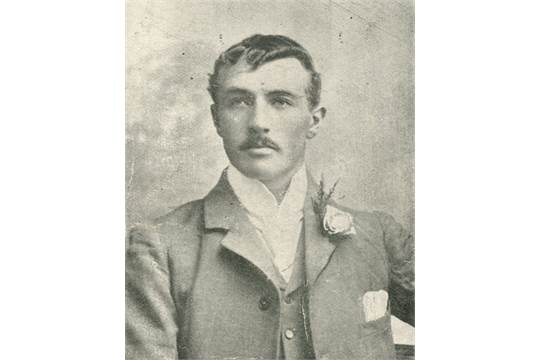

Company-Sergeant Major Frank Naden of the 1/6th Cheshire Regiment

And we also have an account in an interview at the end of December 1914 with Company-Sergeant Major Frank Naden of the 1/6th Cheshire Regiment, which was printed in the Evening Mail in Newcastle on 31 December 1914; he states:

On Christmas Day one of the Germans came out of the trenches and held his hands up. Our fellows immediately got out of theirs, and we met in the middle, and for the rest of the day we fraternised, exchanging food, cigarettes and souvenirs. The Germans gave us some of their sausages, and we gave them some of our stuff. The Scotsmen started the bagpipes and we had a rare old jollification, which included football in which the Germans took part. The Germans expressed themselves as being tired of the war and wished it was over. They greatly admired our equipment and wanted to exchange jack knives and other articles. Next day we got an order that all communication and friendly intercourse with the enemy must cease but we did not fire at all that day, and the Germans did not fire at us.

What is significant about this is that Wyatt and Naden would have been serving with each other in the same place because the 1/6th Cheshires were attached to the 1st Norfolks to be trained in trench warfare. Naden’s accounts also backs up a lot of what Albert Wyatt stated and to me confirms this aspect of what occurred as being accurate.

Guiding the Christmas Truce. I can be seen showing a small group where the 1st Battalion Norfolk Regiment and the 1/6th Battalion Cheshire Regiment met No 16 Reserve Infantry Regiment in no-man’s land on 25 December 1914.

This incident has become something that was put into film in 2014 when the Sainsbury’s advert about the Christmas Truce came out. If you look at the British soldiers in the advert, you will see that they are men of the Cheshire and Norfolk Regiment.

Sadly, the truce did not last, as Herbert Reeve noted:

We went to the frontline the following night and were met with a hail of bullets—an end to any such fraternisation. The High Command took a poor view of this and we were immediately posted further left towards Ypres, at a place called Dranouter.

The argument about football and the truce is something that comes around each Christmas, and people often brag that they have proof that football was played elsewhere, including the area where the UEFA memorial now stands. I have yet to see any evidence of those boasts.

I mentioned right at the start about the two failed attacks that took place on the 14th and 18th December 1914. During a another failed assault on the Bird-Cage, near Plugstreet Wood, a fifteen year old boy was killed. Rifleman 5509 Robert Barnett died in the advance. He, along with a large number of others, were recovered during the Christmas Truce. This is because one of the main reasons the truce occurred was to recover and bury the dead from both sides.

This is predominantly how both British and German troops met in no-man’s land. During this time both sides were able to bury their dead and when you read the accounts of this happening there is no mention of jolly old games of football there is just accounts of mutual respect for the recovery of the dead and talks between both sides where some gifts were exchanged.

But the reality was it was a very sombre affair and once it was carried out pretty much all over the sector the fighting carried on.

When I think of the Christmas Truce I often think of Robert Barnett who, unlike at least one other fifteen year old in this sector, very rarely gets a visitor and does not get a thought in the Christmas period because his sacrifice is overshadowed by the duff history surrounding football and the truce.

The grave of Robert Barnett who now lies in Rifle House Cemetery.

![Sketch map Asiago[1]](https://stevesmith1944.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/sketch-map-asiago1.jpg)